The Beresyit: Essay

The Beresyit

Ipeh Nur and Enka Nkomr

19 August until 19 September, 2016

Krack Studio

The things we fear the most are the things that can’t be named. In Ipeh Nur and Enkah Nkomr’s slippery, creepy, ambivalent images, all those nameless things we try to repress behind the tidy boundaries of modern life come back to terrify us.

This presents a problem for me. My job, as writer and ‘interpreter’, is to provide you with an understanding of their work; to resolve its ambivalence. But what if the whole point of their work lies in its ambivalence? How much should I attempt to translate, and how much should be left ambivalent?

Ipeh and Enkah are young artists from Yogya in the final year of study at the (in)famous Institute Seni Indonesia, Yogyakarta. Both were born and grew up in and around Yogyakarta. Both Ipeh and Enkah’s works have been exhibited in respected Indonesian surveys of young Indonesian artists. Ipeh is a member of the all-girl collective “Tulang Rusuk”. Enkah is also active as a street artist in Yogya.

Enkah’s work is a series of fictional posters referencing musicians, books and movies, as well as religious dogma, Javanese mysticism, pulp fiction, porn and popular culture – the world remixed by his unconscious. Enkah describes his work as Horror. In classic film theory, what always underscores the horror genre is “the return of the repressed”. The central characters struggle to defend their nuclear family values against an immoral, inhuman threat that they’ve locked in the basement. Horror films provide a release valve for our societies to name and face their darkest fears. In a similar way, Enkah opens the door to the basement; to all the things that make us anxious; the irrational, transgressive, ambivalent threats that we try to repress from the regulated spaces of contemporary life. As much as his works are creepy, mystical and malevolent, they are also funny, ironic and critical.

Ipeh’s work is based on the story of “Goyang Penasaran”, an Indonesian horror story written in the 1970s by Abdullah Harahap, and recently re-written by Intan Paramadhita. In the original story, the central character Salimah is a dangdut singer; a deeply sensuous popular music that is sung with the whole of the body. Salimah’s talent is so prodigious that she arouses the desire of many men in her village, but also the condemnation of the local Imam, Haji Ahmad, who eventually expells her for inciting ‘zina mata’ (literally; adultery of the eyes). After several years away she returns, now wearing a long white jilbab. The local head of the village, Solihin, wants to marry her but Salimah knows that what really motivates him is his unrequited lust for her former self. She agrees only if Solihin gives her Haji Ahmad’s eyes as his ‘dowry’.

Abdullah Harahap’s original story is typical of Orde Baru popular culture, in which traditional family values must resist the voracious individualism of the big bad city. Intan Paramadhita rewrites it as a critique of religious conservativism, and as a feminist parable. Ipeh’s revisioning avoids narratives that are redemptive. Her interest is in the visceral feelings that drive us unconsciously; how shame feels, the power that comes from shaming others, the hypocrisy of virtue, the corruption of desire, the fallibility of humans, the bad choices we all make, the thirst for revenge…

Ipeh and Enkah often collaborate. In one of their collaborative works, Ipeh and Enkah have provided instructions for how to have sex. These instructions are overly detailed, sometimes moralizing, other times pornographic, and also funny. Theirs is not a redemptive vision of sex; it is neither an activity undertaken to make families, nor is it an identity legitimized by rights. For them, sex is the messy, wet, awkward slapping of bodies, or our shapeless anxieties of what the other person will think; am I clean? am I dirty? what is expected of me? should I shave my pubes? should I leave the light on?

Their works make liberal use of texts in Bahasa Java, Bahasa Indonesia, English, Arabic and other languages, including made-up ones. No matter what languages you speak, you are never going to understand all of these texts. And the point is not what you do understand, but how much always lies outside of what can be translated.

So; to return to my problem with translation and ambivalence. The myth that underscores ‘cosmopolitanism’ is that the whole world can be Google-translated, and that all forms of difference can be compartmentalized, redeemed and enshrined in rights. But the problem with Google Translate is that it can only translate into a form and language that the audience is already familiar with.

For example, in Ipeh’s retelling of Salimah’s story the jilabab is often featured but its meaning is ambiguous. All at once it’s a garment, a fashion accessory, but it’s also a symbol of purity, of religious devotion or of conformity. But then it shifts at times into a symbol of coercion, or a signifier of Islamic women’s resistance to western liberalism, but also resistance to male sexual violence. It can be read as a symbol of fallen grace, of hypocrisy, shame and for sure many other things. Global audiences continue to struggle with the jilabab because, like Google Translate, they can’t cope with this kind of ambivalence, because ambivalence is precisely what translation attempts to resolve. In clearly defined and regulated notions of identity there is security. In ambivalence there is anxiety.

Contemporary art claims to be ‘global’ because now at every art fair and biennale there are identity-based works from every marginalized community on the planet. This reminds me of those Nineteenth Century naturalists and their portfolios of carefully drawn specimens. Despite their incredible attention to detail, those images always seem so lifeless. In the same way that they turn venomous snakes and lethal spiders into objects of benign interest, the redemptive narratives of identity politics often package ‘difference’ as another new commodity that’s been standardized and certified safe for our consumption.

So the story of Salimah can equally apply to us ‘liberals’ as it can to the conservative men in her village. The world will always be more complex and more confusing than the tidy ideologies by which we comfortably compartmentalize our lives. And there will always be those who exceed those boundaries. We can allow these encounters to transform us, but if not, then don’t we deserve the same fate as Haji Ahmad? What use are eyes if we only allow them to see what we want to see?

In unleashing the monsters in our basements, Ipeh and Enkah challenge us to embrace the uncertainties and ambivalences of contemporary life. A changing world will always invoke our insecurities and our fears, but a world that refuses to change is ultimately more terrifying.

Malcolm Smith, Yogyakarta, 2016

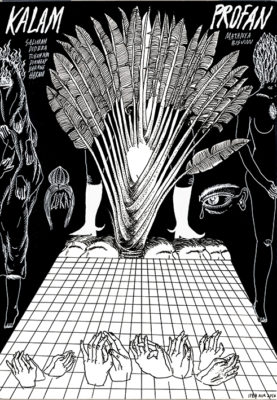

Image Above;

Ipeh Nur, Kalam Profan (2016)

Silkscreen print on offset plate. 37 x 42cm. Edition 2 plus AP

Enkah Nkomr, Sayibatoya (2016)

Silkscreen print on acid free Old Mill paper. 50 x 70cm. Edition of 4

The Beresyit (collaborative works), Poster Kesehatan Beresyit #1 (2016)

Silkscreen print on 100% cotton Arches paper. 53 x 70cm. Edition of 3